- Home

- Stein, Tammar

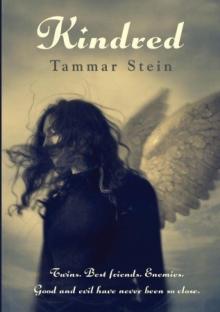

Kindred Page 4

Kindred Read online

Page 4

“First of all, sis, if it was that important, then I think the Big Guy upstairs could have held off another couple of seconds to make sure you two were clear of the falling debris.”

I start to say something, but he goes on.

“Second, maybe the angel shouldn’t have spoken in Ancient Hebrew and in code, don’t you think? What’s wrong with plain English? Why make it a big mystery for you to figure out? You had a lot of hurdles to clear, and you did what you were supposed to do. You should be proud of yourself, not upset.”

I appreciate the pep talk, and I really appreciate that in Mo’s eyes, at least, I’m not a horrible person. But it doesn’t change my basic belief that I was supposed to spare Tabitha pain and suffering and I hadn’t done that.

Mo mistakes my silence for agreement.

“My task wasn’t nearly as complicated,” he says, by way of explanation.

I give him a funny look. “I don’t know that comparing the way the devil works with God’s way is a good tactic to win an argument.” Mo’s truck reeks of something I can’t place. That and his annoying tendency to turn everything into a debate erodes any sense of relief I felt in sharing my secret.

“We aren’t having an argument,” he says. “I just think it’s interesting. Everyone always portrays things as black-and-white, good or evil, but really, what in life is that simple? I think we, as a civilization, don’t have a clear view of what the celestial breakdown is really like.

“Unlike your painful, terrifying encounter, with its confusing task, my visit was very pleasant, almost magical, where everything was revealed and my task clearly explained. He even gave me suggestions for how to do it.”

“Rub it in,” I grumble. “And what did you do?”

“He told me to go to the library and cut three pages out of a certain book. I did. End of story.”

I wait for him to continue, but he just sits there.

“And …,” I prompt.

“That’s it. Mission accomplished.”

“No, it’s not. It can’t be,” I say, annoyed. “You didn’t think to wonder why the devil might want you to do this?”

He looks uncomfortable for a moment but recovers fast, coming right back at me.

“I’m not an idiot, Miriam,” he says, glaring at me. “Of course I wondered.”

We’re both quiet for a second before he continues, defensively. “There was some schmuck who was expelled on honor charges. He was the last person to check out the book for a class assignment, so they figured he cut the pages so no one else could use them.”

My eyes grow round.

“You got someone kicked out of school?” I ask in outrage.

“Whatever,” Mo says. “He was an asshole. He deserved it.”

“Oh, really. Why was he an asshole?”

“He was born that way, okay? Shit, Miriam, what the hell do you want from me?” he says, raking a hand through his hair. We sit quietly in the car, the hum of the heater the only sound. I don’t look at him. “He really was a jerk,” Mo says after a moment. “He even served time in juvie, okay? I checked.”

“That doesn’t make sense, Mo,” I say quietly. “Why would the devil want someone like that kicked out?”

“Look, I don’t know and I don’t care. Nothing is simple in life. We can’t ever know the whole story, so we do what we can to take care of ourselves.” Nothing he says sits right with me. He’s missing a huge point: a kid from juvie who goes to college is special, someone who’s turning his life around, except he’s just been dealt a huge blow and he’ll probably never get another chance. But I don’t know if Mo’s ignoring this because he doesn’t want to see it or because he’s been bedazzled. My lunch, a slice of deep-dish cheese pizza from the dining car, turns uneasily in my stomach.

“How can you say that?” I ask. “My task was to save someone and your task was to ruin someone. The difference matters, Mo.”

Mo, who is studying advertising, has yet another easy answer.

“Listen, sis,” he says, not unkindly. “We’ve somehow tapped into major power. Major. The biggest power there is. You’re with God, I’m with the devil.” He says that like it doesn’t matter which is which. Like it doesn’t mean that one of us is doing evil things. “Do you realize how powerful that makes us? We could rule the world.”

“Now you’re scaring me.” I turn away and stare blindly out the window. It’s fogging up, airbrushing away that dismal parking lot, the urban decay. It still looks depressing. “I don’t think you get it. We’re nothing to them. Tools. Maybe even less than that. We’re totally discardable, paper napkins to wipe their hands with and throw away.”

“I wouldn’t be so quick to say that. They need us. I’ll do the first few chores gratis, but after that, my man downstairs is going to pay.”

“What, like you’re a crack dealer? You’re going to get him hooked on you? Don’t kid yourself.” My brother isn’t evil. I know he isn’t. My twin brother, with my identical brown eyes that always seem like they are laughing, his face as familiar to me as my own. I just have to talk some sense into him. “If it’s really Satan you’re dealing with, he’s had centuries to manipulate people—millennia. Remember that nice little couple, Adam and Eve? Didn’t turn out so great for them. A semester and a half in advertising is not going to bring you on par with the Master of Deception.”

I’m not getting through to him. His eyes are shining, he can’t stop grinning.

“What about your soul, Mo?” I ask, feeling frightened. “Aren’t you scared?”

But Mo isn’t scared. Mo is excited.

I leave after Mo buys me dinner at the student cafeteria. He sneaks out a couple of apples and a roll for me to take. I have to be careful with my money. I emptied out my bank account and have to make my meager savings last until I figure out what to do with my life. But this fine line between sin and mischief, between cleverness and manipulation, haunts me. I accept the smuggled food with mixed feelings.

“Call me if you need anything,” he says, hugging me fiercely. “Though I’m sure you’ll be okay—I mean, you’ve got angels watching over you, babe.”

I give him a weak smile.

“But sometimes,” he continues, “you need a little devil on your side. So don’t forget, I’ve got connections.”

V.

I DON’T KNOW if Mo is right or not. Maybe angels are watching over me. Maybe a bit of his devil’s luck rubs off. Either way, I do pretty well as a college dropout.

My advisor, who was rather shocked when I told him I was taking a “leave of absence,” e-mails me the week after I quit school with the contact information for a small paper in Tennessee that’s looking to hire a full-time assistant.

“Thought it sounded perfect for you,” he writes. “It would help to keep busy and make a bit of money when you’re looking for answers. I know the editor; we were in the army together. I took the liberty of sending him a couple of your pieces from the school paper. He’s interested. Here’s his number. Do me a favor and call.”

I’m torn. On the one hand, the little money I have is disappearing faster than I ever imagined. At this rate, I’ll be broke by week’s end. But then again, I can’t shake the feeling of a giant bull’s-eye on my back. I don’t sleep well at night. I’m scared to be alone. I’m leery of anything that smacks of “destiny” or “fate,” afraid of where it might lead me. Am I supposed to go to this small town in Tennessee? Is this part of God’s plan for me? I don’t dare say no, but I’m afraid to go. I worry daily about another visit.

But finally, after sitting in a diner and ordering the cheapest thing on the menu and leaving still feeling hungry, I decide to call. It’s ridiculous to think that sleeping someplace different every night will actually keep me hidden from whatever God has in mind for me.

One phone call later, I am gainfully employed by the Hamilton Morning Gazette. My new boss expects me to be at work the following Monday, but doesn’t offer to pay for a ticket that would get me to Tenn

essee. Given that my salary isn’t discussed either, I begin to have a fairly good idea that this isn’t a job one takes for the financial benefits. Still, it’s better than what I’ve got now, and it’s nice having a bit of purpose in life again.

I call my parents to report in.

“I’ll be in Tennessee, about eight hours away. I’ve got a job at the local paper there.”

“That’s great,” my mom says with some relief.

“I don’t know that I’ll be writing articles right away, but I’ll let you know when I get published.” Oddly enough, dropping out of college has actually turned out to be a good career move. I’m about to write for a real, commercial paper. It’s a small ray of hope that life as I know it isn’t actually over.

“Okay, sweetheart, I’m glad you’ll be staying put for a bit and not that far away. Are you feeling okay?”

I’d told my mom about the occasional bouts of diarrhea I’ve had. “It’s been clearing up,” I say. “It just took a while to get used to all that greasy school food. Not that I’m complaining; this has been the best weight-loss program I’ve ever been on.”

“You don’t need to lose weight,” she says a bit sharply.

“I’m fine, Mom.”

“I won’t nag, but you need to take care of yourself. Part of being an adult is taking care of the body God gave you.”

Oh, the irony.

“I’ve got to go,” I say.

“Safe travels, my love,” she says. “Call me when you get to Tennessee? I know it’s not part of the agreement, but I’ll feel better if I know you’ve arrived.”

“Okay, Mom. Love you.”

“I love you too, my darling. God bless you.”

He has, I want to tell her. It isn’t nearly as pleasant as you might think.

VI.

MY ADVISOR’S FRIEND is supposed to meet me at the bus station, but I don’t see anyone who matches the image I have of him. I wait until the station clears of everyone except people waiting for some other bus to come.

I’m looking for someone who looks like my advisor, who still wears his military service proudly—buzz-cut hair, ramrod posture. Instead, half an hour later, a short, round man with a flowing Civil War–style mustache bustles through the depot. He looks like a cross between Colonel Sanders and an Oompa-Loompa.

“I’m Frank,” he says as I stand there, my legs stiff and my back sore from the long ride. “Frank Hale. You must be Miriam. And aren’t you a pretty little thing. Hope you haven’t been waiting long.” He looks around with a moue of distaste. “Can’t say the bus station is our most attractive site. Maybe it’s time for the city council to step in.”

“It’s nice to meet you,” I say.

We shake hands, and he holds on a second longer than necessary before reaching for my suitcase.

“Come along,” he says, as if I have been dawdling. “Let’s get to the car and I can show you around a bit.”

I slide into his giant white Cadillac and brace myself as he presses the gas too hard in reverse. The car leaps out of its parking spot like it was stung by a bee. A quick three-point turn later and we’re headed on a two-lane road toward Hamilton.

After fifteen minutes, we enter the town limits and pass a sign that reads HAMILTON, THE BEST LITTLE TOWN IN TENNESSEE! CIVIL WAR HERITAGE SITE. It seems clear the two are related.

Frank, meanwhile, is busy telling me all about my new hometown.

“We film commercials on Main Street about once a month. Folks around here love it. Sometimes they need extras, and you should see the lines in front of the casting tent. They do close down the road to car traffic, and that causes a stir from the local businesses. Still, it’s a bonanza for the town, no mistake about that. Once there was a movie with Johnny Depp that paid for a ten-mile biking trail from the park to the county rec center by the river. He was a nice fellow, that Johnny Depp. An odd duck, mind you, but nice enough …”

I’m exhausted from the bus trip, and his chatter soon fades into background noise.

I wake with a start when the car rocks to a stop. We’ve parked in front of a small yellow building two blocks off the famous Main Street and, according to Frank, not far from the newspaper. Frank hefts my big suitcase and I follow him with my backpack. He unlocks a door and shows me a small one-bedroom apartment. It’s furnished, it’s clean and it’s mine. I love it.

“Now, the gal that lives here got herself a one-year internship in Paris, so I know she’ll be mighty glad to have someone look after the place.”

And pay her four-hundred-dollar-a-month rent, I think, but don’t say that.

“What is she doing in France?” I ask, half jealous despite myself. Some girls get a low-paying job in small-town Tennessee; some apparently snag a job in Europe.

“France?” he says, confused. “Now, why would she go there? She’s in Georgia. Paris, Georgia. She’s doing something with real estate development. Some sort of partnership between us and them.”

“Oh. That’s nice.” The bemused look on my face draws him out of his ramblings. “Hon, you look tuckered out. Why don’t you rest here, settle in, do a bit of exploring over the weekend, and report to work bright and sharp on Monday.”

“Okay,” I say, unbearably weary. “That sounds great. Thanks for everything.”

“Welcome to Hamilton,” he says. He pats my arm and leaves.

I flop on the bed, grateful that it’s made and that the pink flowered sheets smell clean. I managed to mumble through the Birkat Habayit, the blessing for the home, and the Shehechiyanu, the blessing for new events, which roughly translates as: “Thank you, Lord our God, for giving us life, and sustaining us, and bringing us to this day.” I’m still feeling my way around everyday prayer, trying to figure out how much is expected of me, what is a fair prayer. I learned the Shehechiyanu and Birkat Habayit as part of my bat mitzvah training, long evenings sitting at the kitchen table with my father, repeating the Hebrew words after him. Mo hated studying for his bar mitzvah. Only the thought of the massive amount of presents and money he’d miss out on without a bar mitzvah kept him going. As it was, we split the Torah portion reading between the two of us. He took the first three verses, all short, while I chanted the last four, which were twice as long. But I didn’t mind. When I was with Mo, I pretended I hated studying Hebrew too. But when it was only my father and me, sitting in the bright kitchen while night grew heavy outside, we would have the most wonderful discussions about the meaning of a vowel in a word, the trop on a word, the choice of a pronoun or a repeating adjective. Every strange mark, every odd choice, was meaningful to him.

Both my parents looked at religion as a powerful and meaningful way to structure one’s life. My father saw Judaism’s interest in details as a form of worship. The particles of meat that could be left over on a washed plate and mingle with the next meal’s cheese meant that there were separate dishes for meat and dairy to honor the mandate that one should not cook a calf in its mother’s milk.

My mother’s Catholicism meant she turned to Jesus in her daily life: we owed him an impossible debt for saving us from original sin and he looked on us with kindness and mercy. Sins could be and were forgiven with proper repentance, and we must love and serve God in this world.

Neither of them ever lost sight of the fact that God was the creator of all things: the sun, the moon, dancing honeybees, pregnant sea horses, and all the other wondrous creatures that live on earth.

I see now that attention to detail would have helped prevent the pickle I’m in now. I hope that I can be forgiven. My repentance is sincere.

Their shared belief that God is interested in all things great and small—the tiniest detail and the incomprehensible concept of an expanding universe and black matter—leaves me frightened about what will happen to Mo.

I worry and nibble on a fingernail. I’m not sure what I can do about his enchantment with the devil. We’ve texted and e-mailed this past week, but despite his excitement and assurances, I don’t buy his co

nviction that the devil isn’t all bad. I remember the heated arguments he and my dad would get into around the time of his bar mitzvah, Mo claiming that the Bible was the world’s bestselling novel, a great adventure story but a silly book to base your life on; my father, eyes flashing, insisting that the Bible is the word of God. Has meeting the devil only reinforced Mo’s belief that God is irrelevant?

Tired as I am, thinking about my father reminds me I’m supposed to check in. I call him and ask that he tell my mom about my safe arrival.

“I said two prayers when I arrived,” I tell him. There is a pause, and I wish I could see the expression on his face. “It seemed like the right thing to do.”

“B’sha’ah tovah,” he says, which literally means “in a good hour” but is used to say “Congratulations!” I can’t tell if he’s being sarcastic. It always strikes me as odd how he is so devout and so cynical at the same time.

“Okay, Dad. Don’t forget to tell Mom.”

“I won’t. Love you, sweetheart,” he says. The kindness and love in his voice make me doubt the earlier snarkiness I thought I detected. “Take care of yourself.”

I’ve never been much for praying, but those two prayers felt right. Call me crazy, but I suspect there’s more than an even chance that divine intervention brought me here. It seems like a good idea to appreciate that, for the moment, it’s a benign, pain-free intervention. I know how quickly and easily that can change.

My job at the Hamilton Morning Gazette is part errand girl, part copy editor, part headline writer. The bone of contributing to a story is occasionally tossed my way, usually when a stringer has dropped the ball. I have a day, sometimes two, to catch at least three sources willing to be quoted and to verify facts, write a catchy lead and work with the existing fragment until it resembles a six-hundred-to-nine-hundred-word article. Sometimes I even take the photos that accompany the story.

I tell myself that such a well-rounded introduction to the newspaper business is every cub reporter’s dream. Or what they would dream about after the New York Times gave their prestigious summer internship to someone else. I’m learning the ropes, top to bottom—though, if I’m honest, mostly bottom. But really, apart from the fact that my salary is so low that after rent and utilities I have about two hundred dollars a month for food and entertainment, I actually like my job.

Kindred

Kindred