- Home

- Stein, Tammar

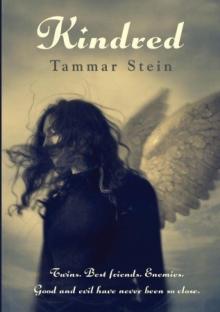

Kindred Page 6

Kindred Read online

Page 6

“The H is for Hamilton?”

“H is for hospital, Miriam. After the battle was over, twenty-eight makeshift hospitals were set up. The battle was fought all around the town. Every house still standing was turned into a hospital.”

“Where did they get doctors from?”

“No doctors. Maybe one or two medics rushing around and sawing off limbs. Mostly it was the lady of each house, using up her linens, drawing water, giving comfort as boy after boy died from their wounds. You’ve seen the cemetery, right? The one behind the Linden Plantation?”

My chest feels tight, and sweat pools under my arms. More proof of God’s distant disinterest. How could such terrors exist? This town no longer seems so cute and quaint. I think of all the buildings I pass every day and the horror that occurred in them. I’d seen glimpses of the old cemetery with its small faded markers, its maple trees and wildflowers, and thought it a peaceful place.

“Think of it, Miriam,” Frank continues. If nothing else, the man loves a good story. “Boys your age dying as their legs were sawed off with no anesthesia, bleeding to death or, worse, rotting from the inside out from gangrene. No antibiotics then, remember.”

“Yeah, I knew that,” I say weakly. And where was Raphael then, that cold healing angel? Where was the meddling, the divine concern that has landed me in this current situation? Once again, I’m shocked and frightened to be singled out like this.

“They were burying them as fast as they could dig. It was the last Southern offensive of the war. After that battle the Yankees took the initiative, so to speak. You all right there?”

“Yeah,” I say, knowing I look pale. “Gruesome, though.”

“Nothing like history to give you a bit of perspective, eh? Now, was there something you wanted?”

For a second I’ve forgotten what I came here for. Then my stomach cramps up and I remember.

“I might be coming down with a bug or something. Do you have the name of a good doctor?”

“Poor thing,” he says, instantly solicitous. “I’m so sorry to hear that. Dr. Robert’s a great young doc, one of the best in town. He’s my aunt’s neighbor. You tell him I sent you.”

In my cubicle, keeping my voice down, I make an appointment.

But even with the name-dropping, the soonest Dr. Robert can see me is in two weeks. I try to convince myself that by the time the appointment comes around, I will be all better. I can always cancel.

On Saturday Frank sends me to the farmers’ market to meet and mingle with the hippie/yuppie/family crowd. It’s my first story assignment. Until now I’ve interviewed a few sources for the other stringer on the paper and done a bit of research. Frank, in his dramatic fashion, declared me ready for the responsibility. The fact that Alex, the other reporter, is off for a couple days isn’t mentioned by either of us.

I call my mom and tell her that next week I’ll have an article.

“Really?” The delight in her voice zings across the phone line and straight to my toes. “Are they online? Maybe I can subscribe—do you think they would mail me copies?”

“Don’t get so excited,” I say, though I can’t help grinning. “It’ll just be a little fluff piece in a tiny little paper.”

“Nonsense,” she says. “It’s your first professional piece and you’re only eighteen.”

“Cameron Crowe was writing for Rolling Stone by the time he was sixteen.”

“And what did he ever amount to?” she asks.

“Mom, he’s a really famous screenwriter and director.”

“I’ve never heard of him.” As if that’s supposed to be an inarguable point.

It’s funny to me that my friends always liked my dad better than my mom. My dad comes across so cool that no one gave me much sympathy when I complained of the ridiculously high standards he set for my brother and me. My mother was a bit aloof with outsiders, which, combined with her past as a former nun, intimidated my friends. But when it was just us with her, she radiated acceptance. No matter what I did, I could never disappoint her. Both my parents are five foot eight, but while my dad seems taller than his actual height, my mom seems shorter. Something about the way they stand and take up space in a room always makes it hard for me to believe they’re the same height. My mom’s short gray hair in a perpetual bowl cut contrasts with my dad’s messy auburn curls—it’s like her hair spurns attention, while his demands it.

My mom didn’t like to talk about her life before Dad, but it wasn’t a secret that she had been a nun for six years before leaving the order. She’d lost her parents in a car accident when she was five and was raised by a deeply religious uncle. She told me she became a nun at eighteen thinking she’d find the home she’d never had. But like many women who marry young, she and her groom grew apart. Life in a religious order was nothing like she’d imagined. Less Sound of Music, more Big Brother. At twenty-four, she left the church with a heavy heart. Three years later, when she and my dad got together, she was getting her doctorate in comparative religion, living a completely secular life. She agreed to raise the kids Jewish; hence my bat mitzvah. It was quite a scandal at my dad’s congregation when the rabbi married a former nun, a shiksa from England. I’m sure the nuns were equally horrified.

Mom would come with us to synagogue and read from the prayer book, speaking the Hebrew words in her proper English accent. I do believe her commitment was genuine, but as we got older, she rediscovered her Catholic faith. After the divorce, she quietly resumed attending Sunday mass.

Faith is something that seems to imprint on you when you’re young. After the divorce, I grew very close to my mom, and part of that meant I went with her to mass. Though my father and I never spoke about it, he must have worried I would convert to Catholicism. But I never found it hard to separate spirituality and dogma. Being raised Jewish had taken hold, and even after my mom began attending mass regularly, even after I started going with her, I enjoyed the spirituality of Catholic service without being confused by dogma.

Obviously the doctrines of the two religions are different, which is why many people can’t look past their incompatibility. Perhaps it’s because I was raised by parents who found a way to reconcile that conflict that I found myself attracted to the sense of quiet gratitude for the beauty and preciousness of life that is such a big part of both services. Catholic worship is also a visual feast. The beautiful stained-glass windows, the robes—even the churches themselves—create a sense of peaceful serenity. I understood why my mother craved it. Nothing else must have ever felt quite right to her. The songs, the words, the language, weren’t the same, but after a few years of reciting the same prayers side by side with my mother, I found the same comfort, the same peacefulness, the same sense of hope that I found from chanting the Kaddish or the Shema in synagogue.

As I hang up the phone, it occurs to me again that if I told my mom the reason I left school, if I told her about Raphael’s visit, she would believe me. I’m not sure if this is a flaw or not, but my mom always believes whatever Mo and I tell her. It used to be a game we played, to tell her outrageous stories about the things we saw on the way to school, the people we met. She would listen and ask questions and never seem to doubt the possibility that maybe we didn’t really meet the president of the United States at school or weren’t really invited to join the NASA program as the first children in space. When I started to giggle and Mo would admit we were “just teasing” or “making a joke,” she would laugh right along with us. The one time we fooled my dad, telling him we’d been expelled from school for refusing to take communion—this was a public school, mind you—he was angrier at the fact that we tricked him than at the thought that the school had mandatory communion.

But I don’t tell my mom the truth. For one, it seems much too late to start admitting I met an angel. For another, not telling anyone (except Mo, and he doesn’t count) hasn’t gotten me into trouble. What if telling my mom brings the angel back? What if this time he’s angry? It was bad enough to meet

him for a routine—if that’s what you can call it—assignment. Having an encounter where he’s angry just might kill me.

The thought that I am being punished bubbles up from the dark, bitter part of my mind, but I brush it aside.

When I call my dad for our weekly check-in, my unhappiness with God comes up in a sort of vague, theoretical way.

“Doubt is built into Judaism,” he says as soon as I tell him I’m struggling. I don’t explain that it isn’t my faith that’s wavering, it’s what to do about my newfound religiosity. “The name Israel means ‘he who struggles with God.’ Notice it doesn’t say ‘doubts’; it says ‘struggles.’ The important thing is to do, to act.” My father is passionate about this, and it’s obvious it’s something he’s thought about. His words give me chills. “The rabbis say we’re judged by our deeds, not our words—and never by our thoughts. So when you have doubt, when you feel anger or bitterness toward God, no one is marking demerits on your soul.”

I wonder when he had his moments of doubt. Perhaps he still does.

“But what if your acts aren’t good enough? What if they aren’t what God had in mind?” I hope he takes this as a rhetorical question.

“That’s just another way of saying you doubt. You can hold on to those feelings, but your actions better be those that follow God’s commandments, that help your fellow man. Do any of us reach our full potential? Is there anyone who could say in all honesty that they couldn’t have done anything more than they did? No. God has set an impossible standard for us. We’re human, fallible, selfish, weak. We do the best we can and live our life. Does that help?”

“No.”

We both laugh.

“There’s this great old saying I learned in rabbinical school that during the day God dictated the Torah to Moses, and at night He explained it to him.” He pauses to let that sink in.

“Then no wonder the rest of us are floundering,” I say. “But I guess that makes sense.”

“Sure it does,” my father says. “Now take care of yourself and call more often. You don’t need a crisis to talk to your old man.” He sounds lonely, and I feel a zing of guilt for not doing more and calling more often. Another thing to add to my list of inadequacies.

“Yeah, Dad.” The phone pressed to my ear is warm. I’m alone in my tiny apartment and I wish my dad were here. “And thanks.”

* * *

The Saturday farmers’ market is held under a large wooden shelter next to an empty parking lot I’d passed several times during the week without paying much attention to it. Now the lot is so overflowing with cars that there’s a crooked line of them on the grass by the side of the road.

I park my car, on loan from Frank. I hear the bluegrass music before I see any produce, and as I hike over to the market, I unintentionally keep time with the lively beat that shakes out from under the massive shelter that houses the market. As I draw closer, I see tables piled with mounds of fresh veggies in shiny pyramids and glorious bunches of wildflowers arranged in bouquets that would make Martha Stewart weep with joy. There are stands selling baked goods, homemade cheeses and crafts. The band, up on a tiny stage, consists of four generations of the Winkler family, as a draping sign proclaims. Toothless Great-grandpa, wearing an I’M THE BOSS baseball cap, plays the bass; Granny and Dad play the fiddle; while the youngest member of the family, a girl of about ten, looks both embarrassed and pleased as she plays the accordion and is sometimes persuaded to sing in a high, clear voice. They sing Civil War–era melodies that must have been sung in this very town for over a hundred years. As I remember the H flags from earlier in the week and Frank’s graphic recounting, the lovely melodies, and plaintive fiddle seem haunting.

I shake off grim thoughts of war and begin jotting down impressions in the small notebook I’ve brought with me: the soft morning air, the scent of crushed basil leaves, the unhurried mix of families, dedicated hippies in vegan shoes and conservative social pillars picking through wildflower bouquets probably intended for their evening’s dinner parties. I’m trying to stay a detached observer, but the market is such fun that I find myself beguiled by it. I tuck the notebook into a back pocket, as I am unable to resist buying spring baby lettuce, a bright, happy bunch of sunflowers and strawberries that smell like perfume.

A deeply tanned woman in overalls bags my strawberries and we start chatting.

“Yeah, I am new here,” I say, answering her question. “I work for the Gazette.” I love saying that. I tilt a hip so she can see the reporter’s pad poking out. “I’m actually on assignment,” I say. “But I’m mixing business and pleasure.”

Her eyes gleam with interest, so I ask her a few questions about her farm, how long she’s been coming to the market and what’s in season. Juggling the bag of produce on my arm, I write down her comments. The bags are slipping, but I don’t want to hug them too tightly, since the lettuce and strawberries could squish. The flowers keep poking me in the eye. I feel a blush coming on; I must seem like such an amateur. There’s a reason mixing business and pleasure is usually a bad idea.

“Your parents must be proud of you, beautiful,” she says, giving me a chance to finish writing her last quote.

I look up from my notepad and smile. “Thanks.”

“You should come by the farm one day,” she says. “Might make a nice story, and even if it doesn’t, you’d like it there.”

“Really?”

“Sure. We’ll put you to work. I can tell you’re a city girl. You should see where your food comes from.”

“Yeah, I should. I’m Miriam,” I say, shifting my packages so we can shake hands.

“Trudy,” she says. “That’s Hank over there.”

She points to a man, wrinkled and tanned, unloading more produce, adding it to their table loaded with big juicy strawberries, long stalks of rhubarb, small mountains of sugar snap peas and a complicated structure of broccoli. He’s tall and thin, like a younger version of the farmer in American Gothic. He’s missing a pitchfork and glasses, and he has a trimmed beard, but he has the same patient look and gaunt frame of the man in the painting. He looks up when he hears his name. I wave.

As I fumble for my wallet to pay for my purchase, Trudy pushes away the money. “This is your welcome present to Hamilton,” she says over my protests. “Come to the farm,” she says again, and squeezes my hand. She gives me a recipe for tomato-and-cheese pie, assures me it’s easy and delicious and turns to help the next person in line.

I leave the market clutching my veggies, my flowers and my first story idea.

I spend the rest of the weekend polishing up the farmers’ market piece. I’ve interviewed a young mom and her three-year-old, his mouth stained bright red from strawberries. A city official has given me a couple of statistics on how much revenue the market brings in, how long it’s been active. I move the quotes around in the story, write three different leads and e-mail my favorite three drafts to my mom, my dad and Mo to help me choose which is best. When they e-mail back with opinions and each with a different favorite opening, I spend another couple of hours debating whether to implement their suggestions or not. In the end, I keep the article as I first wrote it.

On Monday, back at the office, I print out the article and show it to Frank. I hold my breath as he skims it, waiting for his reaction. Less than a minute after he’s started reading it, he nods and puts it down.

“Good,” he says. “We’ll run it Friday.”

I fight to pull off a blasé face, as if I regularly have articles accepted for publication. From Frank’s suppressed smile, I can tell I’m not fooling anyone.

“I think there’s another story there,” I say with studied casualness. “That vendor I quoted from Sweetwater Farm is local. It’s the only CSA farm in the county.”

Frank, now clicking at something on his computer screen, utters a distracted “Hmm?”

“It’s where people pay for the farm costs and then get a share of the harvest. It’s all organic. All local.”

/>

He stops typing and thinks for a second. “Are they hippies?” he asks suspiciously.

“Only a little.”

His tongue pokes around his mouth. He sucks his teeth. I hold my breath.

“Yes, it could work,” he finally says. “Is it safe to presume you’d like to cover this?”

I try to play cool, but my whole face lights up in excitement. Frank laughs. “I’ll take that as a yes.”

“Yes!”

“All right, Miriam. Six hundred words. You have until the end of the month.”

I float back to my desk, grinning like a fool.

I e-mail Mo and my parents, so excited I can barely stand it. This is even better than my first published piece. This is my first story idea. I shoot Trudy an e-mail with the news and ask for a good time to come over for the interview. Although a lot of reporters interview a subject over the phone, or even by e-mail, the best reporting is done when you meet face to face. Plus, I want to see this farm for myself. I’m too wound up to do interviews for a story on the city council’s vote to move trash pickup from Mondays to Tuesdays. I glance through the list of upcoming topics. There’s a rumor that the superintendent is considering putting in metal detectors at the local high school. It sounds ridiculous to me in this quaint town, but maybe there’s a history of trouble I haven’t heard about. I start making notes to research school violence in Hamilton, but before I know it, I get distracted by stupid links and online articles on organic gardening, and then by daydreams of writing a feature on Trudy. I know she won’t answer my e-mail immediately, so when I smell a fresh pot of coffee brewing, I head to the break room.

In his mid-twenties, Alex is the closest to my age among the Gazette’s staff. Of medium height and with a prematurely receding hairline, he’s tanned and lean from the long rambles he takes through the woods, searching for Civil War artifacts. It’s an open secret that he’s working on a novel about the Civil War battle that took place in Hamilton—the bloodiest three hours of the war, or whatever Frank had called it.

Kindred

Kindred